28.10.2024 (Caucasian Journal). Our guest today is Jan KOMÁREK (Czechia), Professor of EU Law at the University of Copenhagen and Visiting Professor at the Charles University in Prague.

▶ ქართულად: The Georgian version is here.

Alexander KAFFKA, editor-in-chief of Caucasian Journal: Dear Jan, welcome. We have been looking forward to this interview in particular because of the crucial importance of the legal aspects in the EU integration process. And, on the other hand, the legal side of things has the most direct impact on the public.

Let's begin with some fundamental questions: What happens to an individual's rights when their country joins the EU? Do people become better protected? What options are available if there is a conflict between national laws and EU laws?

Jan KOMÁREK: Thank you for having me for this interview. But let me correct one premise of your question first: Law does not have such an immediate effect as you suggest. The change is slow and gradual and depends very much on who the people in charge of applying and enforcing the law are. And if a new country joins the EU, these are the same officials as before, responsible for its daily application, whether in the public administration or in courts.

True – and that is mentioned in the second part of your question, EU law creates more ways to be enforced than e.g. international law, including some rights of individuals in certain situations. However, if you mean fundamental/human rights, these are – at the European level – mainly protected by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, and Georgia has been a party to the European Convention for a long time already. The EU will not change so much in that respect.

The change is slow and gradual and depends very much on the people in charge of applying and enforcing the law.

What the EU adds (with its judicial system) to the protection of fundamental rights is complexity. The European Court of Justice in Luxembourg is, and this needs to be stressed, an institution of the EU, while the former court, the one in Strasbourg is the key institution of the Council of Europe – a different organization, which encompasses a lot more states, including e.g. Turkey or Switzerland. Even Russia was a member before it was excluded after its aggressive attack on Ukraine in 2022.

Now all these courts together with your national constitutional court would interact in a complex game of authority, which may be exciting for lawyers (after all, complex laws give them jobs), but from the point of view of “ordinary people,” this can make everything even more remote and less tangible, especially if they expect that everything will change overnight when their country joins the EU.

The previous president of the European Court in Luxembourg Vassilios Skouris stated in 2014 that “the Court of Justice is not a human rights court; it is the Supreme Court of the European Union” – meaning that its main task is to enforce the authority of EU law, not to protect human rights; and the current president, Koen Lenaerts does not seem to be thinking anything different about this.

The focus of the present Court – besides lots of questions that concern the interpretation of the multitude of rules that the EU has adopted in so diverse spheres – is the rule of law as the key EU value; we sometimes seem to be going back in time, when (Western) Europe seemed to be united into a “Community of Law” (“die Rechtsgemeinschaft”, the term promoted by the first European Commission’s President, Walter Hallstein).

AK: Can you provide some interesting cases to illustrate this?

JK: Sure, I said that EU law protects some fundamental rights in certain situations, with emphasis on “some” and “certain”.

Hungary, ruled by the autocratic/oligarchic regime that Orbán had gradually established since 2010, is a case in point. Out of the many things that his government did in violation of some basic premises of EU membership were systemic attacks on civil society and universities, especially those supported by George Soros since 1989.

One such law was even dubbed “Lex CEU”, as it was clearly aimed at the Central European University, which has been providing liberal education in the region and space for research in social sciences that mattered at the international level, attracting, naturally, academics and students highly critical of Orbán and his regime.

Lex CEU was eventually reviewed by the European court, but we must not overlook that the grounds for that Court’s jurisdiction were provided by the fact that Lex CEU affected the right of establishment and also obligations stemming from the rules of the World Trade Organization. In the absence of such a link it would be hard, I think, to get this case to the ECJ on the “mere” grounds of the violation of academic freedom, protected by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In other words, the EU fundamental rights are still dependent on other EU rules, they are never the single and final objective.

The EU fundamental rights are still dependent on other EU rules, they are never the single and final objective.

If you wanted a full legal explanation for this, we find it in the Court’s Opinion from 2014, which effectively blocked the EU’s accession to the European Convention. The Court then said that “the interpretation of fundamental rights is ensured within the framework of the structure and objectives of the EU”. What are these? Again, to quote the Court: “the free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons, citizenship of the Union, the area of freedom, security and justice, and competition policy”. No mention of fundamental rights, which is not something to blame the Court for. It has been intended by the Member States to be like this.

Note also, that the case related to the CEU got to the Court through an action raised by the Commission and concerned a well-known institution, endowed with foreign investment: There are not many cases where it was a “small individual” who got protected in Luxembourg against their government.

The case just pending before the Court may show whether this is still true: In 2021 the Hungarian Parliament adopted a law that prohibits or limits access to content that portrays so-called ‘divergence from self-identity corresponding to sex at birth, sex change or homosexuality’ for individuals under 18. The Commission took Hungary to Court for violation of EU fundamental values. So, strictly speaking, no link to other goals of the EU (such as economic integration) does not need to be established, if the case succeeds.

AK: We know that compliance with EU laws is always monitored. For example, “The Czechs are a solid, let’s say, average,” - said Vera Jourova, the EU Commissioner for Values and Transparency, comparing the state of the rule of law with other EU countries. So, apparently, some countries are closer to EU law than others, with varying levels of harmonization. Which country's alignment with EU law is considered the best, and which is viewed as the worst?

JK: In general, the Nordic countries tend to be among the best, while the countries of the South, especially Italy, the worst. I think it has to do with the overall rule of law and democratic culture– including, importantly, how strong and fair state institutions are, and to what extent they are trusted by the citizens.

AK: How do you evaluate the current Czech position in the sphere of the rule of law? Also, how do you assess the progress achieved since your country joined the EU? Which areas have seen the most progress, and where are the weakest areas?

JK: OK, I know you are mainly interested in law and legal institutions, after all, I am a law professor in the first place. However, law, especially constitutional law has to do with justice, including social justice, which still has a rather bad name in our part of Europe after the decades of the Communist Party regime.

So, growing up in the 1990s I remember that the traditional liberal rights which center around the rule of law seemed to be the most important in our imagination. We have made a lot of progress in that respect, being fortunate, I think, as we could rely on the democratic tradition (or myth) of our inter-war republic (1918-1938) and especially the figure of our first president, the humanist philosopher Tomáš Gariggue Masaryk.

What we wanted to forget on our way to the EU in the 1990s were the social struggles of that same period: the Communist Party was among the three or four strongest in the Czechoslovak Parliament (known as the National Assembly) and it won the elections in 1946, which were still considered free and legitimate by the standards of that time.

Why do I mention this? Because while the accession to the EU was certainly the victory of liberal values and the confirmation (so much sought for) that our country belongs to the West, from the point of view of social justice, equality and possibly even the quality of life of a large part of population the evaluation is much more complicated.

We, along with other post-communist countries, joined the EU and its internal market primarily as a source of cheap labor – which could compete primarily with its low expectations regarding labour and social protection standards, while in many countries whole sectors of industry were closed, forcing people to move to the West. They are accused of “social dumping”, as they lower these standards for everyone. At the same time, people from the post-communist Europe are sometimes “welcomed” with racist prejudices.

We, along with other post-communist countries, joined the EU and its internal market primarily as a source of cheap labor.

Rarely do the people in the West realize that leaving one’s own country is almost never the first choice: The term “Euro-orphans” is used in some Eastern European countries to refer to children whose parents spend most of the year working in farms, the tourism industry, or care institutions in Western countries. These parents typically see their children only for brief periods. I believe that if there were enough job opportunities available in their home countries, these families would not choose to live in such a way.

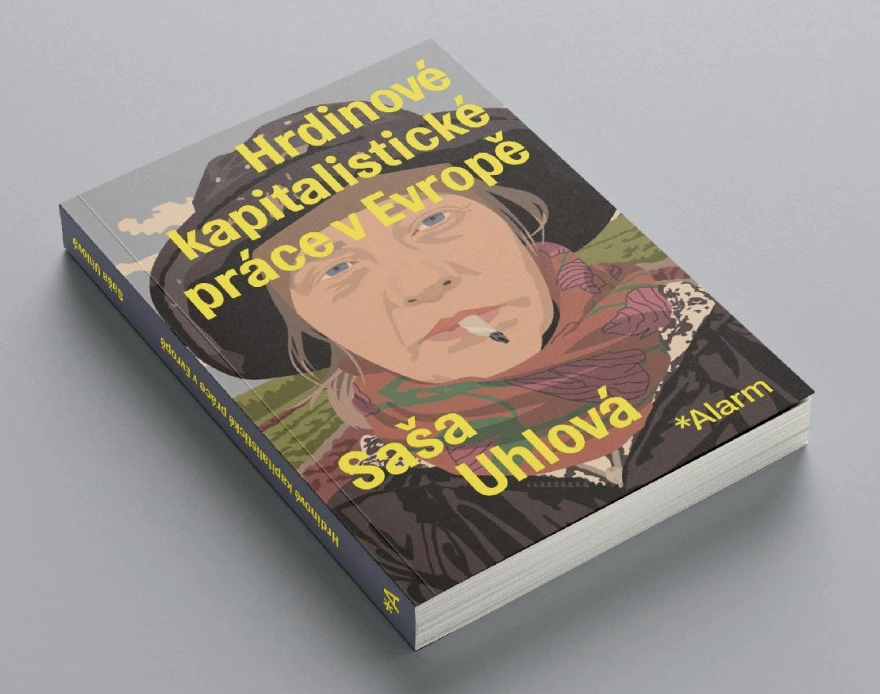

There is a brave Czech journalist Saša Uhlová, who made herself employed in such jobs for several weeks in each, to understand the lives of those workers. The series of reports she wrote (and filmed) was called “Heroes of Capitalist labor in Europe” (a play of words with the title known in the communist time, “heroes of socialist labour”). I hope the book is translated into English, as it shows what integration to Europe ALSO means.

AK: Speaking about not only Czechia, but possibly other comparatively recent EU members’ experiences, can you think of any important “lessons learned” that might be useful to the new candidate countries?

JK: I think this relates directly to what I said above: I think the most important lesson is that by joining the EU the struggle for justice does not end, it only takes different forms. The problem can be, that especially fighting for social rights, fair work or even human dignity is difficult in post-communist (post-Soviet) countries. The language we use is corrupted by the many years of the Communist Party regime. I know that “social justice”, let alone “class struggle” both sound horrible in Czech to someone who still remembers banners that we had to show on the parade celebrating the Labour Day of 1 May.

Within the EU there is a lot of injustice and even oppression: It is more benign than in a totalitarian regime, but it exists.

Secondly, all this is not intended to say that it would be better to stay outside the EU: the membership – alongside with that in NATO – makes all the difference between Ukraine and all three Baltic countries or even Poland. The lesson simply is that even within the EU there is a lot of injustice and even oppression: It is more benign than in a totalitarian regime, but it exists.

So the lesson can be not to present the EU (and the West) as an Eden for everyone, but rather the best of what the country can choose although it is never ideal. Perhaps not so appealing, but that avoiding disappointment with the actual membership.

AK: When comparing the new EU admission rounds with the previous ones, do you believe there are any significant differences? Is the "spirit of Europe" the same as it was 20 years ago, or have there been changes?

JK: Well, one also needs to be honest: in the 1990s there was a real desire and a much more favourable geopolitical situation for enlargement than there is today. So you also need to prepare yourself for the status of a candidate country that may last quite long. Turkey applied for membership in 1987, became a candidate country in 1999 – and is still waiting to be admitted. But, it benefits from this status as well, and that can be what awaits Georgia – and you should be realistic about it, I am afraid.

AK: From a professional standpoint, what are the most critical issues or contradictions in the EU's legal field? What potential issues might arise in the future? Are there any concerns or warnings for new candidates?

JK: I think this relates to what I was talking about before: the EU has become a Union of 27 very diverse countries: the cleavage between the West and East is just one of the many; think of the various ways in which EU member states are affected by the migration pressure (I resist calling it a “crisis”, as it lasts almost a decade), this related to the climate catastrophe and the costs that are, once again, not distributed equally across the continent, etc. It would be great if new members of the EU were not admitted only as a source of cheap labour, natural resources (think of lithium, the key strategic resource in the transformation of energy production) or as a buffer against Russian aggression. Acceding with dignity and respect is the greatest challenge of any new member state.

Acceding with dignity and respect is the greatest challenge of any new member state.

AK: Is it necessary to work towards harmonizing the EU's constitutions? If so, what steps should be taken in this direction?

JK: I do not think they need to be harmonized. I believe the EU can continue to exist only so long as there are ways to challenge the central authority of the EU executive (and also judicial) authority. I have not changed my mind even after what has been going on in Hungary or Poland. Having a strong central constitution would be counter-productive for the long-term legitimacy of the EU.

AK: If there is anything else you would like to share with our readers, the floor is yours.

JK: It was a pleasure, I do not think I have something more to say. Thank you for the great questions.

AK: Thank you very much!

No comments:

Post a Comment